T Level and A Level Results Day 2025

England’s A level results this year tell a blunt story about opportunity.

Top grades rose nationally, yet the gains were concentrated in London and the South East. One in three entries in London achieved A* or A, compared with fewer than one in four in the North East, where results remain below 2019 levels. Ministers have promised to tackle these entrenched divides through a schools white paper.

Ofqual has been clear that the rise in top grades reflects cohort performance and subject shifts rather than grade inflation.

And, unfortunately, the same dataset shows that T levels remain a tough sell: they have a dropout rate of 27% and continued low take-up.

So for anyone working in education, skills, or government, this is a moment to rethink how to communicate impact. Policy is moving fast. Government wants to hear credible stories about how employers, colleges, universities and other local leaders are widening access to good choices at 16 to 19 and beyond.

The Purpose Coalition has always shared its best practice reports openly, so that no-one who wants to make a difference has to reinvent the wheel. Our partners are doing good – and all companies should.

What the 2025 results signal for social mobility

Place matters more than ever. The regional gap – with London’s top‑grade share up by five percentage points since 2019 while the North East is flat – means that if you’re not going to school ‘in the right place’ there’s an increased chance of not meeting the threshold for selective courses, higher apprenticeships and competitive jobs.

Qualifications carry different social signals. One in five working-age adults holds at least one BTEC, but the family of awards remains under policy pressure in England. And that tension shapes how young people and employer perceive non-A level routes.

The technical route is fragile. T‑levels are still less popular than A‑level PE and have high non‑completion rate. If they are truly to reach parity of esteem, employers and providers must address placement capacity, transport and wraparound support.

The takeaway is simple: grades open doors but they track wider social and economic divides.

The government says it is serious about opportunity. It will want to spotlight and learn from partners who make choice visible and viable for students outside the usual hotspots. This is an exciting policy landscape to be involved in, particularly as the readily available solutions we and our partners have identified give proven, scalable templates to government.

T Levels in 2025: promise, friction, and how to reach parity

T Levels were designed to offer a high status technical pathway with real employer currency. The idea is sound. But the friction is visible.

Completion is the headline risk. With a 27% non completion rate across the first cohort, confidence falters. Young people read signals fast. If peers drop out, word travels. So until completion is consistently high, T Levels will struggle to win the benefit of the doubt.

Placements are the fulcrum. The selling point of T‑levels is a substantial industry placement. That is also the operational pinch‑point. Reliability, travel and equipment costs are not marginal issues for low‑income learners: they are make‑or‑break. The learners who most need a credible technical ladder are the least able to subsidise a shaky one.

Parity needs clarity on destinations. Students need certainty that a T‑level leads to a named occupation or a respected degree route. Employers need confidence that the programme yields job‑ready entrants. BTecs’ wide labour‑market footprint shows why destination clarity matters.

The policy question is therefore not about whether or not to back a technical route. It already has.

The question is how to make it so reliable, respected, and clearly beneficial that, for the young people it suits best, choosing it feels like the obvious and safest decision. That requires building trust in the outcomes just as much as designing the curriculum.

The opportunity lens: four tests for the next year

Government rhetoric is clear. The goal is opportunity by default, not by exception. To make that real, four tests should guide any discussion of reform.

Distribution, not averages. National averages look healthy, but regional data shows a widening spread. Policy and practice should be judged on how they change the tails of the distribution, especially in places where grades remain below pre‑pandemic levels.

Routes‑neutral language, routes‑specific design. Stop the tired academic‑versus‑technical debate. The right route is the one that gets a learner to a positive destination. And support each route based on its specific needs – from teacher supply in academic subjects to reliable placements in technical courses. Every pathway needs to deliver for the learners it serves best.

Real stories need to be told. Opportunity is real only when a student can freely pick the route – academic or technical – that fits their goals and circumstances, and see it lead to a tangible result. Government should spotlight specific learners any policy refresh has benefitted, as well as universities and employers who have created opportunity in their communities.

Confidence is a policy variable. When learners and parents believe a route works, participation follows. That is why visible completion, clear progression and employer endorsement matter more than any new acronym or White Paper.

Three uncomfortable truths worth saying out loud

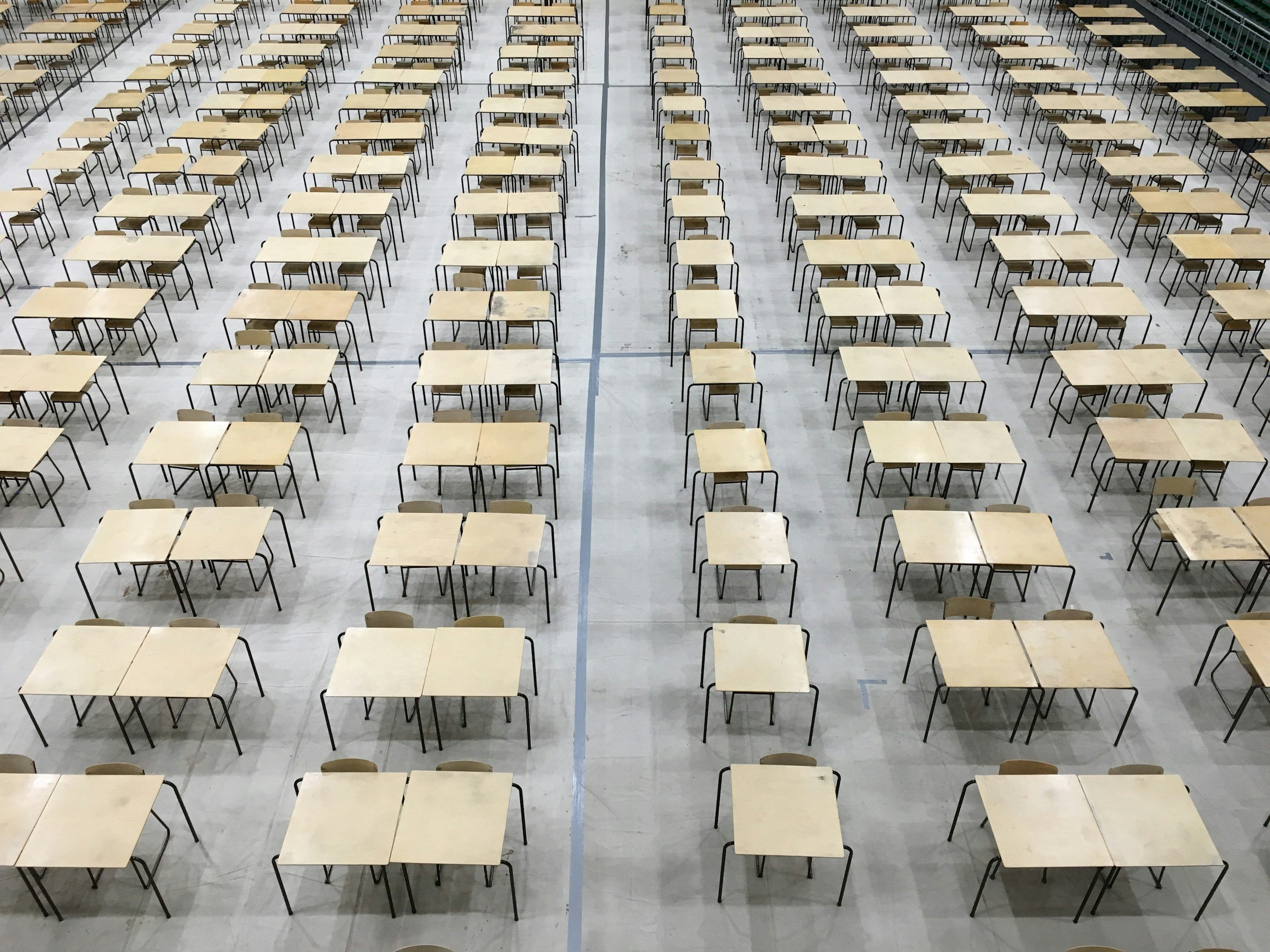

You can’t mark your way to equality. This year’s rise in top grades is positive, but it didn’t narrow the regional gap. A stronger cohort will always look strongest where the ecosystem is already rich in subject offer, teaching supply, and social capital. So policy needs to focus on the invisible scaffolding, not just the exam hall.

T Levels won’t scale on good will. Placements at volume require boring reliability: transport, timetables, supervisor time, predictable onboarding – and placements themselves. Until those are routine and accessible, dropout risk will remain stubborn.

University still carries cultural weight. Participation has risen from deprived areas and a degree remains a strong asset for social mobility. But university shouldn’t be seen as the default marker of success at the expense of technical and trade careers. The opportunity challenge is to raise the visibility and status of every route so that success is recognised in every form, not just one.

What should we be watching between now and exam season 2026?

Firstly, the white paper’s treatment of place Does it prioritise interventions that change outcomes in specific areas where results are still below 2019? Or does it default to system-wide levers that smooth the average while leaving opportunity gaps untouched.

Second, there needs to be a credible completion plan for T Levels. Look for practical measures on travel costs, placement reliability, and equipment access. If completion rises and destinations become clearer, the narrative will change quickly.

Third, subject access in cold spot schools and colleges. The rise in entries to maths, physics, and economics among young men mattered this year. But the real test is whether students outside hotspot areas can access and succeed in these subjects without moving or long commutes.

And lastly, we should watch how Wales and Northern Ireland move. Both saw rising top grades among smaller cohorts. Divergent approaches across the UK can surface workable ideas, especially around technical routes and regional access.

Where the Purpose Coalition sits in this conversation

The Purpose Coalition helps the debate stay practical. Businesses, colleges, universities, and local leaders all see different parts of the problem. But when brought together through the Coalition, those perspectives combine into practical fixes.

And when our partners speak with one voice about a specific barrier in a specific place, government can act with more confidence to back it.

You can learn more about our Purpose Lab initiative here.